Following new sanctions against Iran and Venezuela resulting from increased tensions with North America, the US faced increased pressure to improve oil and gas production. The Permian Basin has played a pivotal role in the US’s recent oil and gas growth. In H2 2018, the country overtook Saudi Arabia in production levels, becoming the biggest crude oil producer in the world. Considering the country’s dependence on imported oil just a few short years ago, this major shift will impact global economies. However, while there has been a boom of oil-rig productivity in the Permian Basin, the market is hypothesising that a bust could be on the horizon as the result of overproduction and saturation within the area.

Hydraulic fracking involves injecting “fracking fluid” containing water and sand into a wellbore. This creates fissures in deep-rock formations, through which natural gas, petroleum and brine flows. With a significant increase in companies vying to compete in the oil space, business operating efficiencies have been impacted. Market research suggests private investors looking to purchase Permian-based companies should first ask how many wells are being created per mile-by-mile section – the golden number is thought to be 3-4. Any more than this increases the risk of channels being created, which causes breakthroughs from one well to another. Unfortunately, well breakthroughs are becoming increasingly common in the Basin. Although high-density sections offer high-volume, short-term oil output, the wells are quickly spent requiring new wells to be drilled more frequently. When channels are created, the rock drains quickly and lowers pressure in the area. This increases the gassier deposits in the cracks, meaning a higher proportion of gas is created compared to oil. Companies generally prefer a higher ratio of oil over gas as profit margins for the former are substantial – for example, producers such as Callon Petroleum aims for 75-80% oil.

Our research has demonstrated that the maturing market could lead to a sizeable upsurge in collaborations, mergers and acquisitions, with three real options available in the industry: the acquisition of midstream water-management companies; smaller, privately owned companies being acquired by larger companies; or collaborations between companies in broken acreage areas.

The first option for companies looking to merge or acquire companies involves oil and gas companies acquiring water management specialists. While most companies are focused on oil production, as previously mentioned fracking naturally creates gas and water, and these byproducts are quickly being considered as lucrative opportunities for midstreams, i.e. those involved in the processing, storing and transporting of oil and natural gas products. Salt Creek Midstream was formed from a joint venture between ARM Energy Holdings and PE group Ares Management and is an early adopter of this model. Its management of water assets has caused Salt Creek to gain multiples, which is likely to cause other businesses to adopt the technique. The market indicates Fortune 500 company Targa or the diversified Energy Transfer are in a good position to acquire a water management specialist like Solaris Water Midstream, WaterBridge or NGL Water Solutions Considering the purchase and disposal of water is one of the costliest elements in the fracking process, companies with recycling water facilities will see heightened margins.

It should be noted, however, that some areas of the Basin are more profitable than others for water management. Water volumes decrease substantially when drilling ceases in a region. This has already been experienced in southern Delaware, where there has been a 30% decrease in rigs as companies move operations to northern Delaware, which is thought to offer better acreage. Considering WaterBridge predominantly operates in southern Delaware, it could face falling profits within six months unless it can act quickly. However, this is likely to be a cost-intensive process, especially considering the labour involved with inserting new pipes in the area.

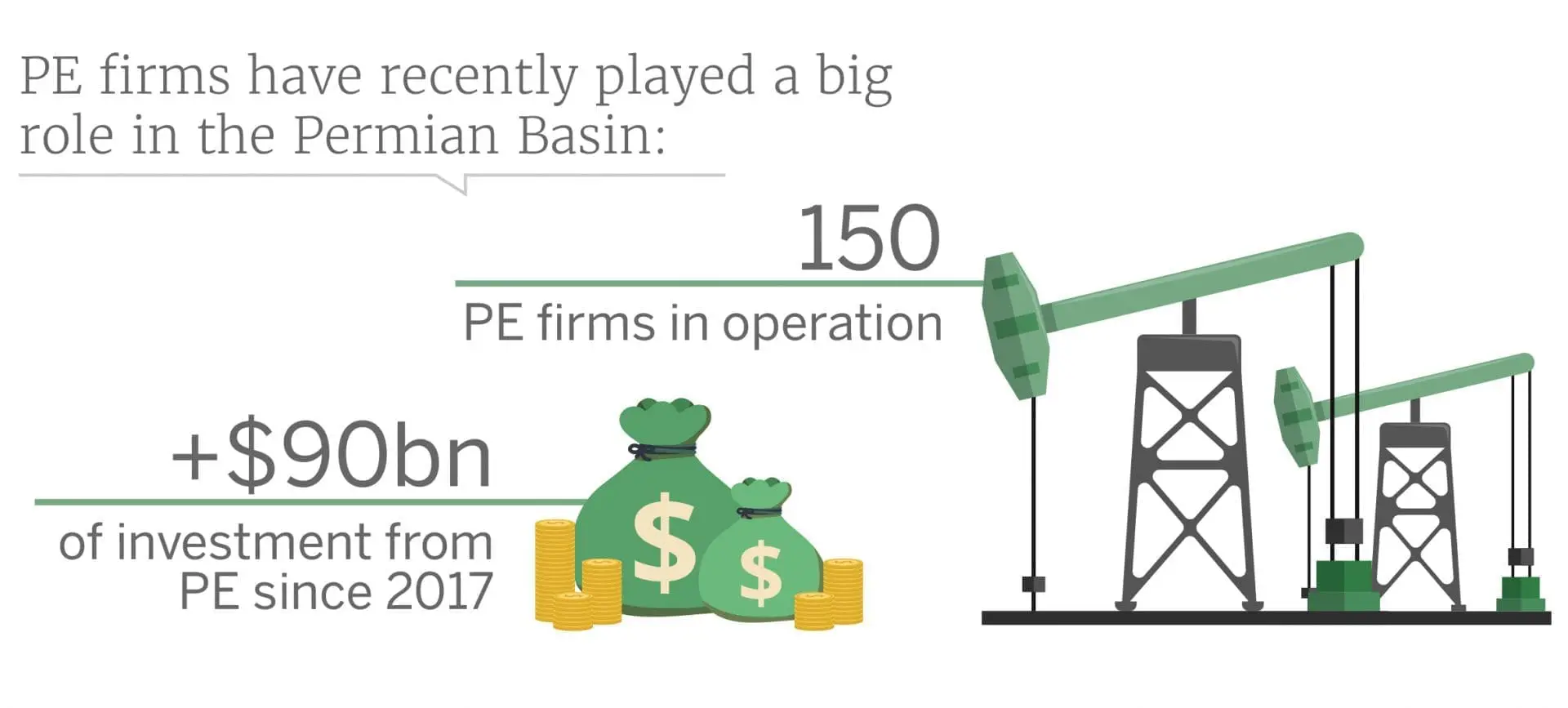

Pipeline construction offers private equity firms a viable option for investment as gathering pipelines are integral for transporting wastewater away from wellsites. Wastewater is currently a USD 34 bn. business within the oil and gas industry, however, trucks are still predominantly used in water removal, so developing pipes to transport water from a wellsite to a storage tank would improve efficiency. If PE firms were to invest in the pipeline industry instead, this could prevent privately owned midstream businesses entering the now-saturated space as they would not have the capital required to enter the market. However, given the saturation of the oil and gas market in the Basin, public companies are becoming more attracted to small, specialised, private midstream companies anyway as they are able to nimbly adjust production levels in response to commodity price issues. This would reduce competition in the area, potentially preventing over-drilling and creating continuous acreage.

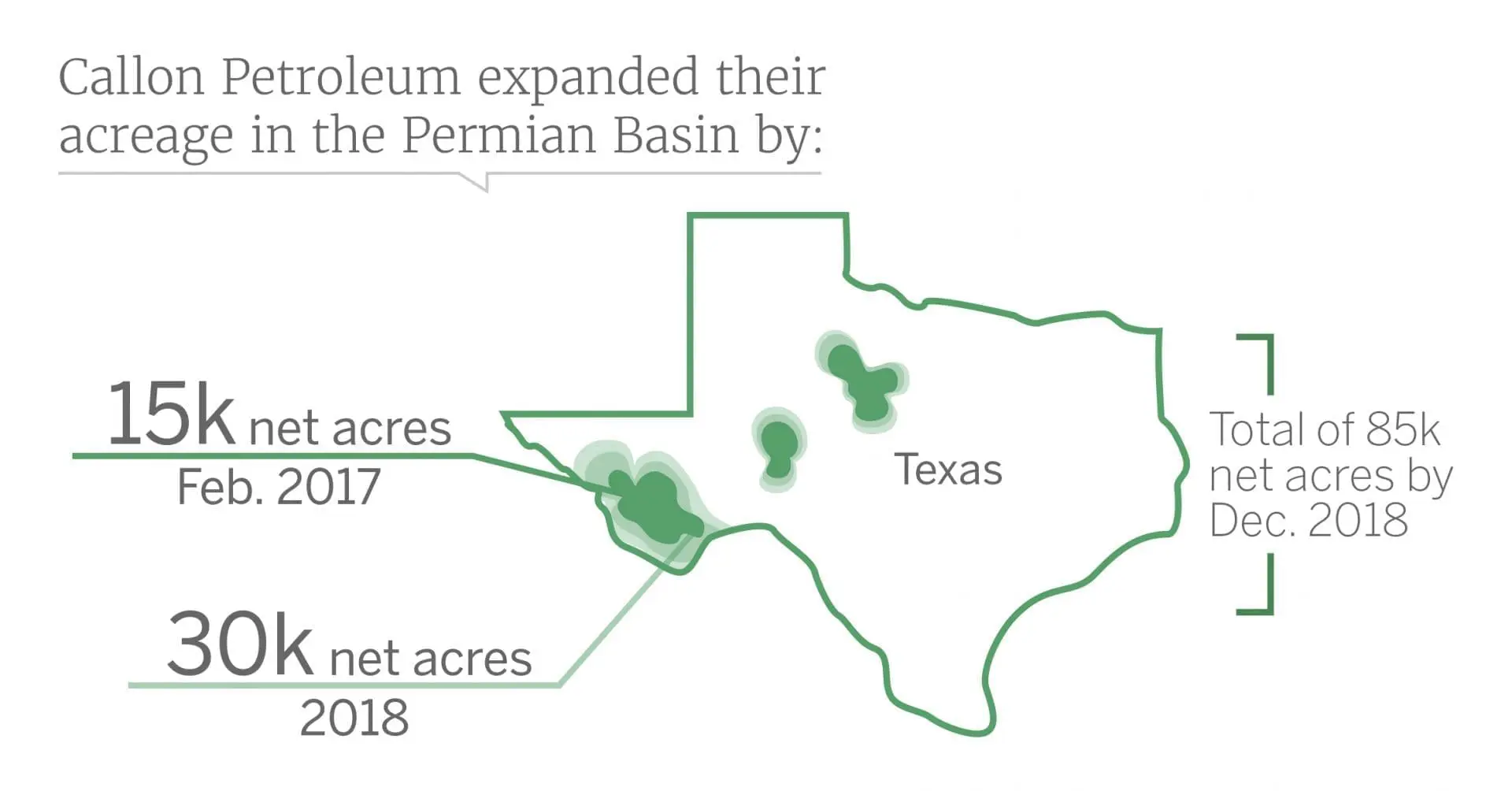

Continuous acreage is where businesses have unbroken acres of land. When land is broken, companies are not able to effectively control well density, which in turn reduces efficiency. However, broken acreage can oftentimes improve collaboration between companies. For example, there is significant opportunity for Callon Petroleum to collaborate with neighbouring companies on joint projects in the Spur, Monarch and WildHorse areas. Historically, this has helped companies focus on joint development strategies, paying closer attention to the value offered per well. Collaborating businesses are unlikely to create high-density well sections as they tend to more seriously consider development strategies, which would improve the position of inefficient companies.

The information used in compiling this document has been obtained by Third Bridge from experts participating in Forum Interviews. Third Bridge does not warrant the accuracy of the information and has not independently verified it. It should not be regarded as a trade recommendation or form the basis of any investment decision.

For any enquiries, please contact sales@thirdbridge.com