Fueling decisions with expert insights

We accelerate and enhance decision-making for investors and business leaders, unearthing the specific expert insights they need across every sector, geography, and topic.

Real insights from real people

No industry or topic is too niche – our global team of 1,500 colleagues across 12 offices will custom source experts and qualify them to precisely match your project’s requirements.

Our research teams build deep relationships with the most sought after experts, so you can access impactful, and well-founded points of view on any industry, market, geography, or topic. We apply rigorous governance and industry-leading compliance measures to ensure that every interaction is secure and all content is fully vetted to mitigate risk.

Your extended team

We collaborate closely with you to understand your specific needs, business model, and workflows, so we can deliver a fast, personalized service and become an extension of your team.

We’re continuously developing new services and digital tools to streamline your search and discovery of information – and to deliver those insights directly into your existing workflows and systems.

Instant access to knowledge

Explore the world's largest collection of on-demand expert insights and company intelligence covering over 65,000 public and private companies.

Our bespoke AI search and summarization capabilities give you access to an abundance of investor and analyst led interviews, complemented by our vast database of private companies including maps of their value chains.

One partner, all the insights

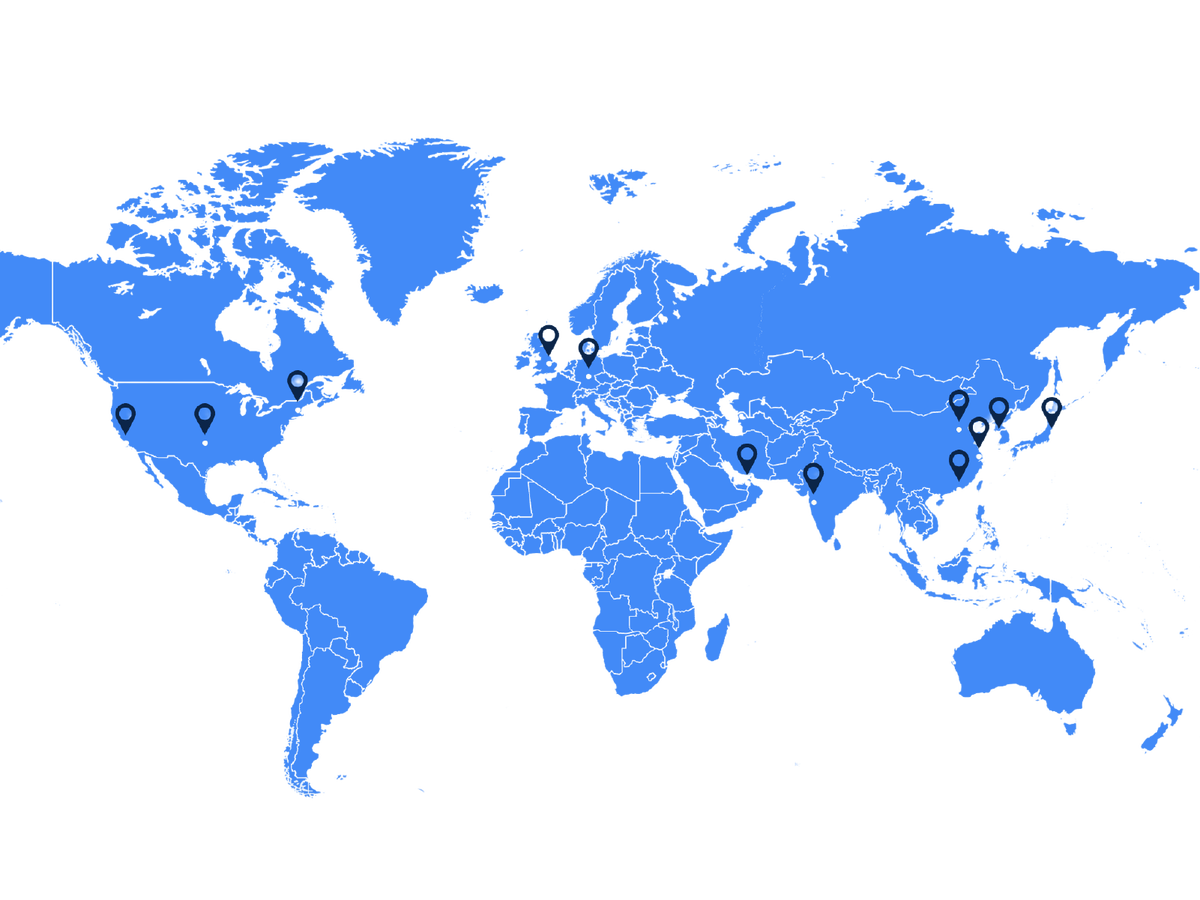

As an industry pioneer, we’ve been serving the world’s top consultancies and investors across every stage of the deal cycle for almost 20 years. Today, our global footprint spans four continents, providing global knowledge localized to your needs.

We use our collective geographic, industry, and company experience to custom source the best experts for your specific requirements while giving you access to the world’s largest Library of company intelligence, 1:1 Expert calls, and Surveys to confirm expert insights at scale.

Trusted by the world’s decision makers

Third Bridge helps us ask better questions during diligence because we're more informed. Without fail, this leads to a better outcome for us and our Limited Partners.

We look at companies dealing with enhanced risk exposure, so extracting nuanced information directly from those in the know is critical to success. Third Bridge is an absolute must-have for us.

What we like about Third Bridge is that it often takes our attention away from the consensus opinion pushed by other research providers, and that's where we typically get ahead of the market.

The speed and relevancy of transcripts and experts Third Bridge provides is unparalleled. You are often our first port of call for this very reason, and we trust you throughout our research process.

I see this as a useful tool for me to educate myself before meetings with companies and it allows me to have a deeper understanding of certain markets. In terms of coverage, I feel like there is enough content for me to load up on helpful information and be dangerous in meetings.

Our services

-

Expert calls

A direct conversation with experts who have the industry insights you need.

-

Library

Instant access to expert knowledge.

-

Surveys

Access critical intelligence with speed and precision.

-

Advisors

Enhance your team with deep expertise.

-

Data feeds

Integrated access to global insights.

Our clients

-

Consulting firms

Access insights. Make stronger recommendations.

-

Private equity

Understand the opportunity. Identify the risks.

-

Public equity

Differentiated insights to outperform the competition.

-

Credit

Understand Issuers. Gain an informed view of credit risk.

-

Investment banking

New perspectives. More mandates.