用专家洞察赋能投资决策

我们为投资者与商业领袖加速决策进程、提升决策质量,深度掘取跨行业、跨地域、跨领域的专属专家洞察。

真人真知,洞察未来

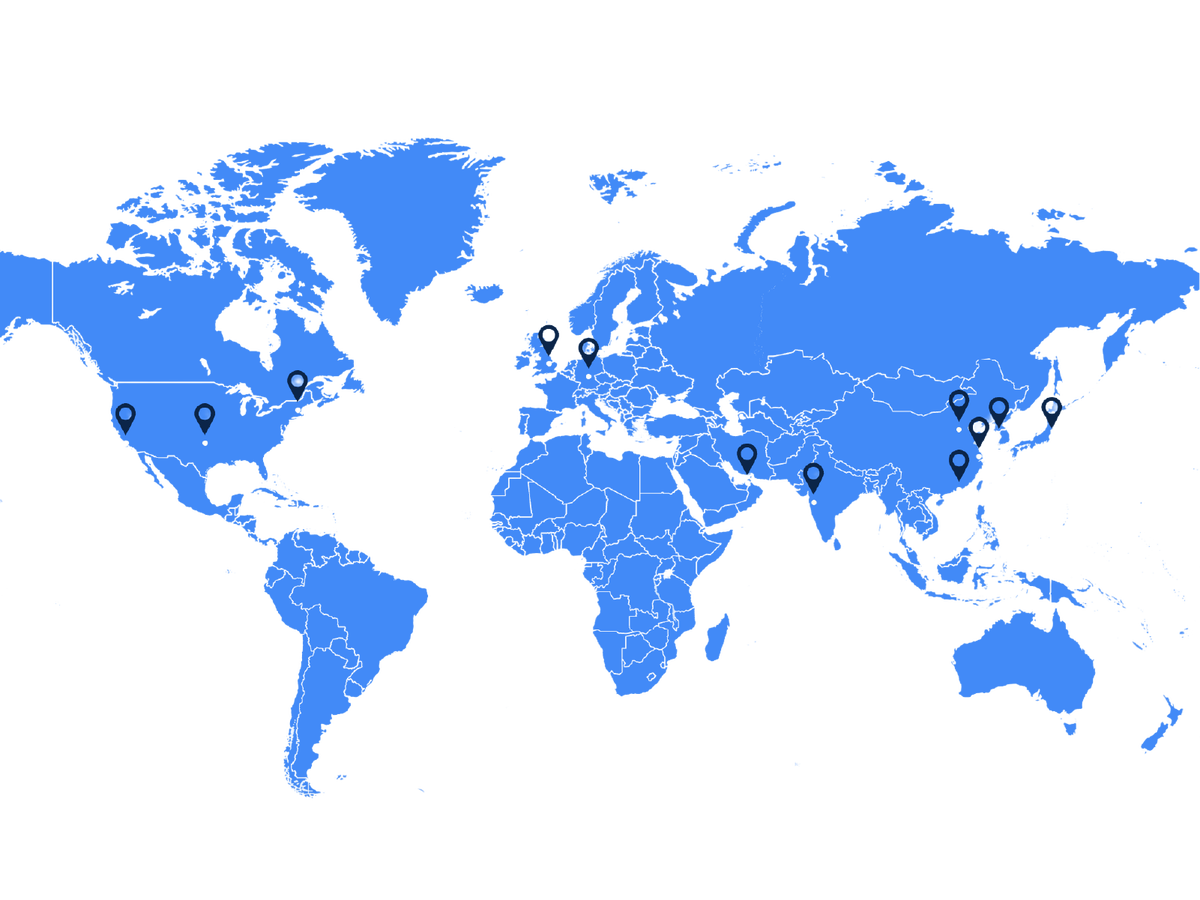

无论行业领域是何等细分或小众——我们遍布全球12个办事处的1,500名专业人员将为您定制化遴选专家,并严格评估每位专家资质以准确匹配您的项目需求。

调研团队与优质专家建立深度合作关系,助您获取针对多个行业、市场、地域或主题的真知灼见。

我们执行严格的治理体系及高标准的合规措施,实现安全可靠的互动,且内容经过全面审查,以降低风险。

您团队的延伸

我们与您深度协作,以便把握您的个性化需求、商业模式及工作流程,从而提供高效定制服务,使我们的团队成为您自身团队的自然延伸。

我们持续开发新型服务与数字化工具,以优化您的信息检索与发掘流程,并将这些深度洞察直接对接到您现有的工作流程与系统。

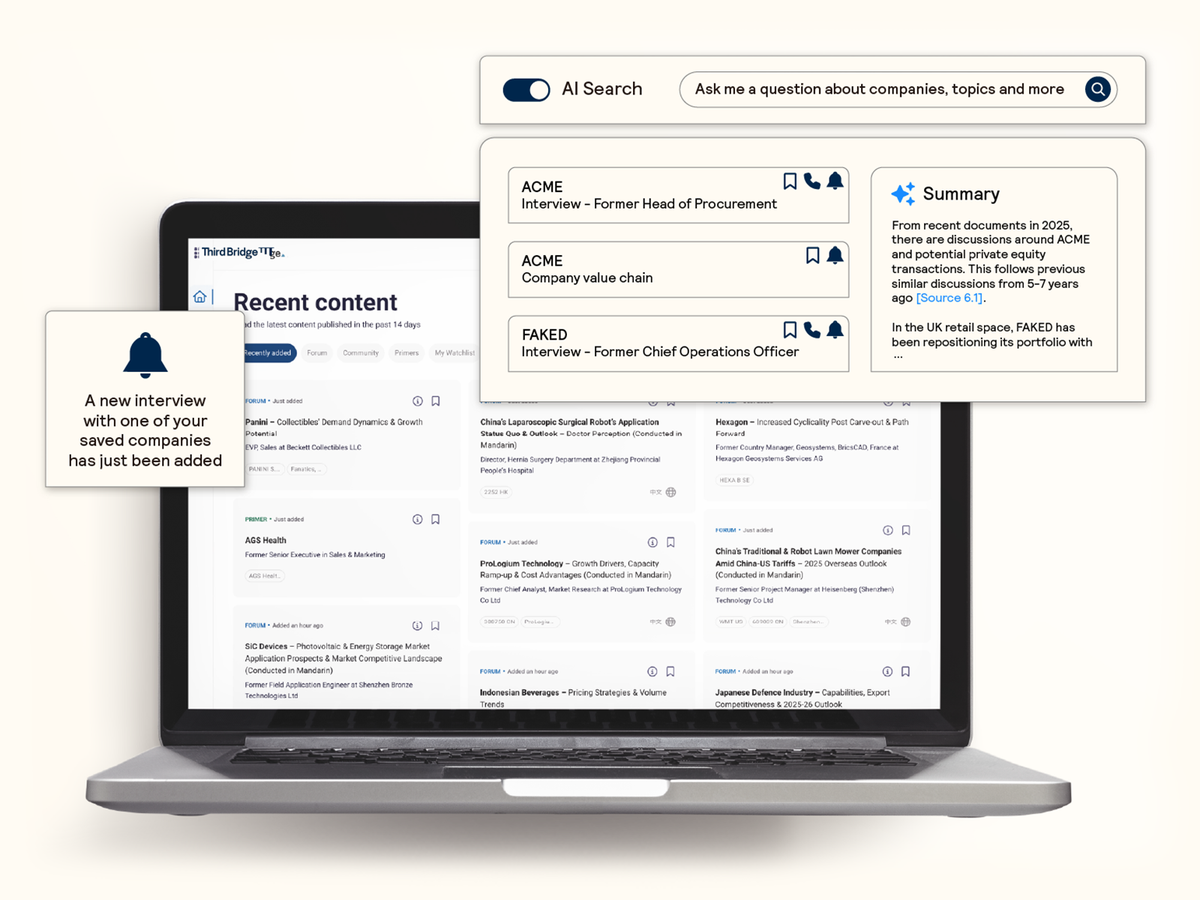

随时获取行业知识

按需获取广泛的专家洞察与公司信息,覆盖65,000余家上市公司及非上市公司。

我们定制化的AI智能搜索与摘要生成技术,为您提供大量由投资者和分析师主导的访谈资源,并辅以包含公司价值链图谱在内的非上市公司数据库。

一个合作伙伴,全面洞察视角

作为行业开拓者,近20年来我们持续为全球领先的咨询机构及投资者提供全交易周期服务。如今,我们的全球业务跨越四大洲,提供符合您需求的广泛知识。

我们依托团队在地域、行业及公司层面的综合经验,为您定制化遴选匹配您需求的专家资源,同时提供丰富的公司信息、一对一专家访谈及规模化调研,以供系统性验证专家洞察。

全球决策者的信赖之选

有了高临的帮助,我们在尽职调查时可以提出更好的问题,因为我们掌握了很多信息。毫无疑问,这对我们公司和有限合伙人都大有裨益。

我们着眼于那些面临更大风险的公司,因此直接从知情人士那里提取细节的信息对成功至关重要。高临对我们而言不可或缺。

高临最让我们欣赏的一点在于它往往能够另辟蹊径,让我们听到主流声音以外的观点,从而抢占市场先机。

高临提供的访谈记录和专家服务具有良好的时效性与相关性。正因如此,高临往往是我们首选的合作对象,我们在整个调研过程中都对其充分信赖。

我认为这是一个实用的工具,能帮助我在与公司会面之前进行自我提升,并深化我对特定市场的理解。就内容覆盖面而言,我觉得现有资料足够我获取有价值的信息,使我在会议中能够游刃有余。